Tools of Radical Studies: Walking in a Shifting Image

In 2021 Al Maeishah was invited by KUNCI Study Forum & Collective as education practitioners to share their tools, among others who developed experiences through collective learning practices, to be publish in a contribution for MARCH Journal of Art & Strategy (read the introduction here).

The following text, outcome from a conversation between Elena Isayev and Diego Segatto in autumn 2021, is published at page 92 in the printed and digital publication downloadable here.

– Walking in a Shifting Image

*

Collective Dictionary is a series of publications containing definitions of concepts inspired by our background in Campus in Camps (2012–2016). Collective Dictionary originally considered fundamental terms for the understanding of the contemporary condition of Palestinian refugee camps. As we played an essential role in its conception and evolution, Al Maeishah now uses the Collective Dictionary as a broader tool to manifest a form of collaborative knowledge springing from the journeys. During each experience, participants choose a concept to highlight and collectively assemble personal reflections.

Campus in Camps (2012-2016)

www.campusincamps.ps

*

The Office of Displaced Designers (ODD) is a collaborative platform for skill-sharing and the coproduction of knowledge for designers who have been displaced and/or marginalized, and local host communities. ODD supports interdisciplinary projects related to and/or impacting the built environment, protection issues, social cohesion, cultural understanding, or integration.

www.displaceddesigners.org

*

Diego Segatto

Looking at Al Maeishah[1] in practice, there are two aspects that make the term “pedagogy” doubtful to me. The first skepticism is about “teaching” and the second one concerns the employment of a “methodology.” Quite programmatically, the name Al Maeishah suggests a different outlook. In Arabic, the meaning of Al Maeishah is the living process. This vague openness allowed us—a small group of three friends randomly meeting—to leave the doors of thinking and practicing to embrace any radical intuition or move that could bring us together, in our different specificities, to make a learning experience happen.

Our keystone of communal learning deploys a proposal, a way of doing, based on a processual and unrushed reciprocal fulfillment rather than on a systematic closed procedure. In the end, what we seek is to connect with other people to tackle the urgencies related to displacement, diaspora, and citizenship, while focusing the gatherings on topics based on the interests of the participants, who are the conveyors of personal experiences and perspectives. We have always valued the meshwork of relations and stories woven into every conversation as a possibility to defy identification based on nationality, citizenship, or privileges imprisoning people through biased and preconceived ideas. I personally see the meshwork of stories as a “pluri-versed” perspective made of different points of view, which are the outcome of our encounters, enabling us to challenge even the perception of the nation-state.

How does it start? We look for inviting situations that give us the possibility to converge. With this publication, KUNCI opened up for us the possibility to do so through the act of writing. I would love it if the readers could join us in a brief walk together. Through this imaginary walk, we can collapse the distances for a moment and make some considerations around such primordial, yet enriching, practice in motion.

Elena Isayev

The kind of walking we draw on in Al Maeishah is a way of making place, “a collection of stories so far,” as Doreen Massey describes it.[2] Place is a cultural system that positions people in the world. At any given moment, it is the creation of multiple imaginaries, as well as the culmination of a shared understanding. Simultaneously a pause in motion and a juncture, it is changeable and, as shown by Pierre Bourdieu, forever reconstructed through practice.[3] It also changes us, “not through some visceral belonging (some barely changing rootedness, as many would have it) but through the practicing of place, the negotiation of intersecting trajectories; place as an arena where negotiation is forced upon us.”[4] Walking is a form of such practice through inscription in time and a tracing in space through movement, which leaves a part of yourself there, while reciprocally place and that moment embeds itself into your being.

Walking here is not only intended as the act of moving one leg in front of the other over a solid surface but can equally be performed using wheelchairs, small oared boats, snowshoes—any way that we propel ourselves through the land or seascape using human energy at a gentle pace that allows for moments of sharing, joint reflection, and pause en route. It is through these acts that we seek the possibility of moments for collective learning and the exchange of knowledge and experience, by allowing for the chance encounter and the emergence or disappearance of preceding inscriptions that are offered by the surrounding environment. It is a way of exchanging rather than replacing stories. As no one can claim a walk, it is fluid and allows for movement as a group and yet to be part of a discourse as an individual. These are intimate moments of discovery—conspiratorial and quiet or, conversely, exclamatory—which draw the attention of all.

Diego

However, whenever Al Maeishah is requested to present a proposal, there is an unspoken game of host and guest. The guest, as the “performer,” is often expected to deliver the show at the center of the stage. We are no exception. From the beginning, we have tried as much as possible to erode the sense of exceptionality around the “outsider” arriving in the place to introduce, steer, illuminate—or, worse—to extract knowledge. As much as the three of us obviously take the responsibility to roll the dice, break the ice, or launch a first provocation, the issues on the table are often still too elusive or incommensurable to land in a fluent conversation. Sometimes silence fills—or empties—the room for minutes and, honestly, I find that state of suspense quite generative toward expressing and freeing disbelief or doubts. But again, in order to be the participants of the experience—in the sense of mujaawarah[5] —we quickly invite those participants to take a collective walk outside and transform suspense into something else.

Elena

The elasticity of the method and its informality is not conducive to hierarchies, even if someone emerges as a guide—that role becomes shared and exchanged as stories come to the fore along the route, which is cumulatively prescribed by the walkers, the landscape, and the stories. In this way, it allows for the suspension of expectation and disbelief. The drifting, which the walk with others encourages, allows for a kind of mental and social freedom from discussion of large, complex, and pressing subjects by focusing on what surrounds.

Diego

To better understand, I can specifically recall the Collective Dictionary entitled Xenia (2017),[6] a booklet that resulted from a collaboration between the Campus in Camps program and the Ancient Journeys and Migrants course at the University of Exeter, where Tom Murrie’s contribution was inspired by a section from Cicero’s De Legibus (On the Laws). In Cicero’s work, an imaginary discussion takes place between Cicero, his brother Quintus Tullius, and their friend Titus Pomponius Atticus as they walk through his family estate. Tom’s “Moving Places: Modern Dialogue” and “Moving Places: Ancient Dialogue” were engendered by our collective coast walk from Branscombe to Beer (Devon, UK). They express how participants connected past and present through a brilliant game of mirrors, redefining an experience of their own by challenging multiple dimensions: the proximity with unknown people, the pleasures and fatigue of the crossing, getting inspired by nature and communality, enhancing self-consciousness, or expanding the view, to name a few. In doing so, I fully perceived how the school—meaning the institution—was reshaped for a few days into a school of people—meaning a group of living organisms orchestrating their movements to synchronize.

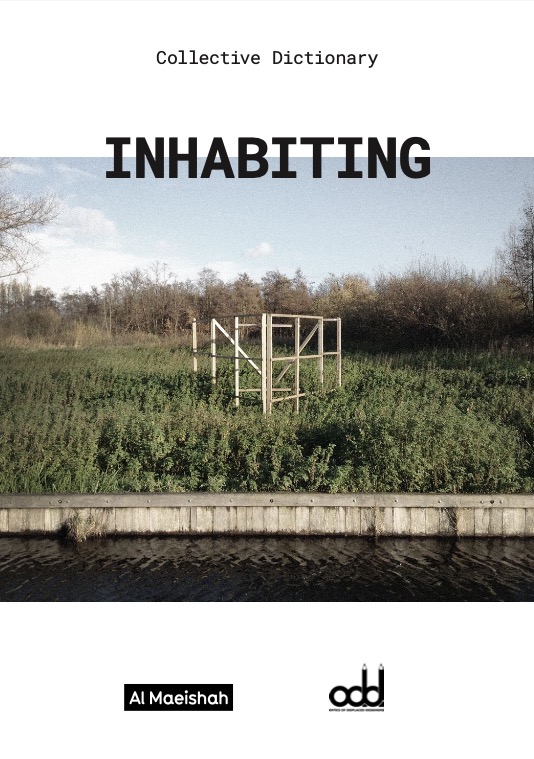

Being in Lesvos, Greece[7] was quite a different journey. Invited by the Office of Displaced Designers (ODD) to contribute to an “alternative” atlas of the island, we found ourselves in a

deeply discouraging situation where we touched with our bodies the narrative of Fortress Europe and the sickness it spreads. It was only once the group of participants was formed (from the Moria and Kara Tepe camps) and we asked ODD to guide us on a few walks, that all of us together could surprise ourselves through sharing personal stories and perceptions of the environment (natural and human). The challenges and chances of inhabiting Lesvos were hiding behind that same synchrony missing between Europe, Greece, the world, and the ravaged countries from which the refugees escaped. The two walks created a space-time to talk freely and live outside of the institutional framework or humanitarian aim, also gifting people with some long-lasting friendships. Personally, I think that for the three of us, it was also a moment of trauma that we didn’t discover without some injuries. I mean, to connect with such a peculiar space-time, in place and not from our safe homes, demands a lot of bending . . . that space-time has so much gravity to bend your perceptions and feelings, if you allow me to use a “psycho-scientific” expression.

Elena

The richness, excitement, and challenge, as well as pain, that can come from such practices of placemaking—a walk, which has its risks—was summarized in the Collective Dictionary volume Inhabiting (2018), written with the Office of Displaced Designers, which is a collection of findings following a series of such walks that we inhabited together during our time in and around Mytilene on the island of Lesvos.

We were fortunate to have a guide, Hassan Tabsho, for one of these walks, who generously offered to share the route he took when going between Moria camp and Mytilene city. It took in histories, vistas, and winds, informing our thinking about what it meant to inhabit. Hassan’s words, which became the essay “Changing Impossibility,” were in response to the view in this image.[8]

The scenery around us.

The surprise—not a scene in a museum

but in real life

taking the best view on the hill.

Can this scene cause more damage to people

who have already been exposed

to war or other suffering?

These remains could still benefit.

But not here.

Maybe inside a museum

or special place for them.

So that the story—not forgotten

Helps to remove it from real life.

These tellings speak of difficult, unresolved, or displaced pasts and their caretakers. They expose how stories live in landscapes, are vocalized, materialized, intertwine, and impact everyday life. They foreground the potential for archival practices to provide shared custodianship, spaces for dialogue and multiple narratives. They ask: Whose story will continue to be told? How will it be told? And who is silenced?

Such moments of tellings, confrontations, and building on each other’s point of view, forming a meshwork, become a form of collective learning in its broadest sense, embedded in interactions. The Chinese-American geographer Yi-Fu Tuan’s formulation that “if we think of space as that which allows movement, then place is pause; each pause in movement makes it possible for location to be transformed into place.”[9]

Diego

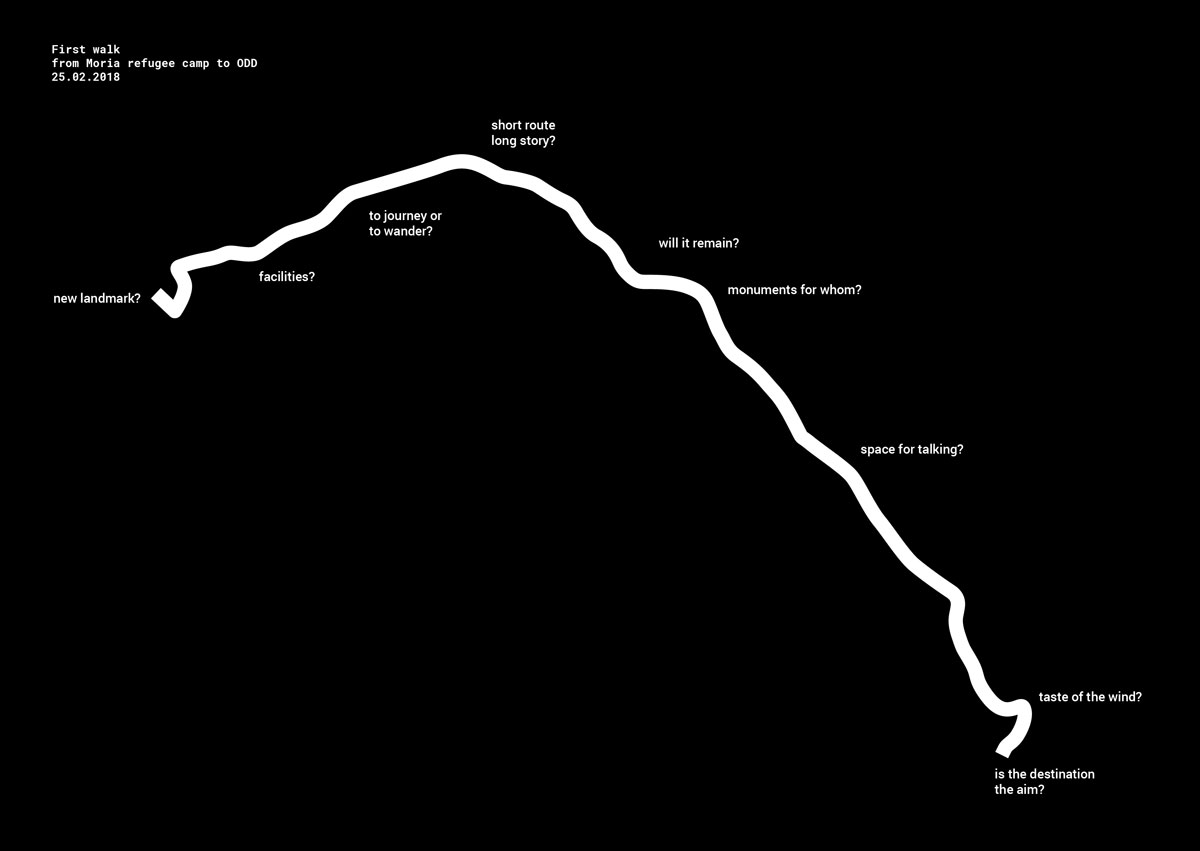

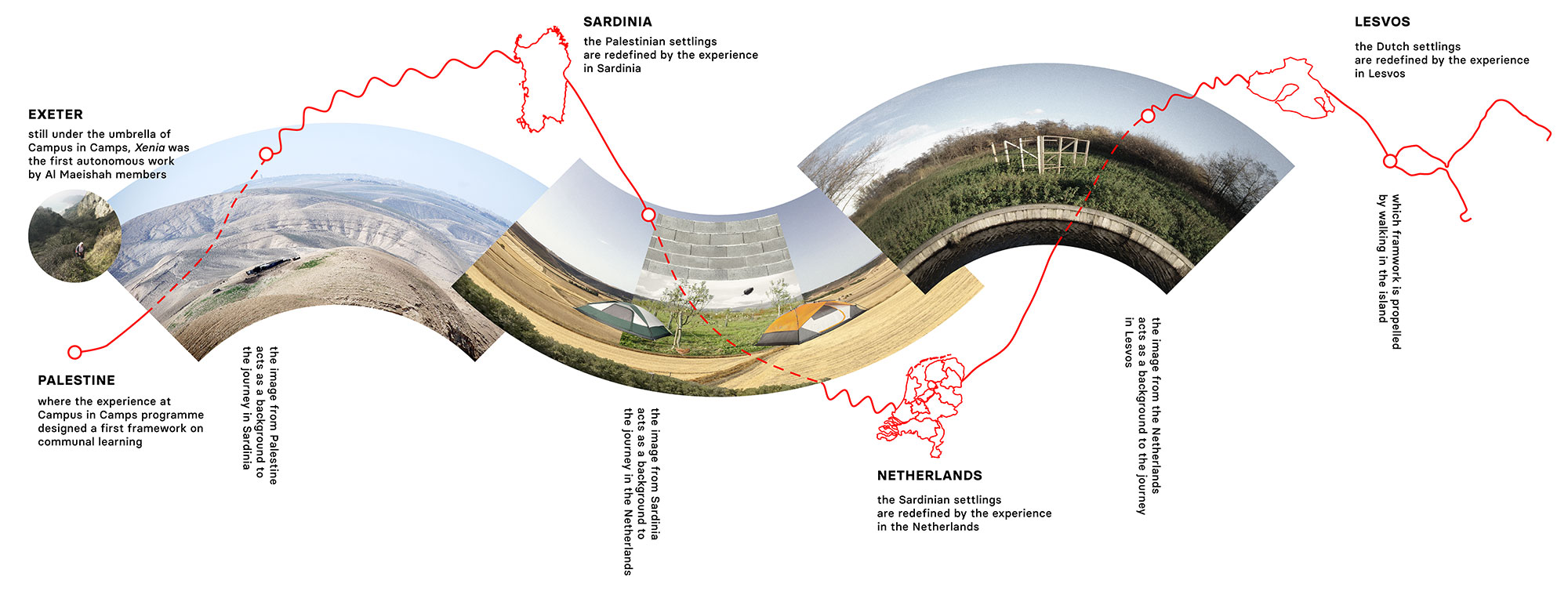

This brings me to look at the shifting image, a sort of device to mobilize imagery that we adopted for the three journeys (so far) as one unique image from a past that is simultaneously recalled, bent, distorted, and redefined by the place of arrival (that we temporarily named the biosphere, lacking better jargon). The shifting image operates as a “portal” triggering possibilities and impossibilities, where the possibility stands in the existing connection among the natural environments, and the impossibility emerges from the human experience we (pretend to) evoke or recall. It is uncanny how from Palestine to Lesvos, every image holds something of the previous ones, in a way—from a Bedouin village as seen from far away through the desert and a neglected nomadic settlement in the synaesthetic Sardinian space to an ephemeral structure alongside the well-organized Dutch canals. It seems as if, step by step, we tried to erode rather than interpret the anthropic presence in favor of the habitat and free movement. Considering Al Maeishah’s premise, it comes full circle.

Elena

It is a kind of reprieve; talking about the walk, which allows difficult subjects to be addressed indirectly with new perspectives, through the shifting image.

Diego

Hence, I’ve never seen the shifting image as a tool (much less walking or assembling) but rather like old tricks—you know they work, in some way, but you don’t really know precisely how they will work or how to control them exactly. Because the rules of the game are declared at the very beginning, an atmosphere is set up. This is nothing new really, like the vast literature about “rituals” or the slippery chapter of “participation.” I think the kind of erratic chemistry we hold and bring, though, makes the real difference. Our experience shows that the shifting image didn’t work very well for the few one-day “workshops” we ran so far, while it made a difference for residential programs lasting at least a week. Perhaps there need to be multiple conversations to build trust in order to walk together time and again, to ease into the exploratory space. If the charm of it is appealing enough for the participants, then we aim that everybody feels legitimated in articulating their views and considering the others, where the main benefit is to stare at a broader color wheel of reality and build a new chemistry, a new realm of mutual exchange, and, even temporarily, a new basis of coexistence.

–

[1] We use diverse spellings of the Arabic term: Al Maeishah, in narration, and Al Maisha, in short form.[2] Doreen Massey, For Space (London: Sage, 2005); Doreen Massey, “The Conceptualization of Place,” in A Place in the World? Places, Cultures and Globalization, ed. Doreen Massey and Pat Jess (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 45–85.

[3] Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1977).

[4] Massey, For Space, 154.

[5] To convene, we rely on mujaawarah (“gathering” or “neighboring” in Arabic). It is an integral part of life, where people converse about actions and experiences, critically reflect on them, and in so doing, gradually and freely build personal and communal meanings and understandings. It requires physical presence and can only happen between mureedeen and muraadeen: between those who want to learn in reciprocal ways.

[6] Available at: http://www.campusincamps.ps/projects/xenia/.

[7] Also spelled Lesbos, Lesvos is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea.

[8] Hassan Tabsho, “Changing Impossibility,” with photographs by Aref Husseini and Enayat Foladi, in Inhabiting: A Collective Dictionary, a 2018 publication by Al Maeishah with the Office of Displaced Designers, available at: https://viewalmaisha.org/ghorfat/lesvos-2/.

[9] Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977), 6.